CONTENTS |

|

| SEPARATION AND INTEGRATION :

TOWARDS A COMMUNION OF CHINESE MINDS AND HEARTS 離心與向心 :眾圓同心 By YU Kwang-chung 余光中 |

|

|

FIRST SNOW OF A RIVER TRIP 江行初雪 By LI Yue 李渝 Translated by Yingtsih HWANG 黃瑛姿 |

|

| NOT A DREAM 不是一夢 By Ai Ya 愛亞 Translated by David van der Peet 范德培 |

|

| BEST OF BOTH WORLDS :

WISTERIA TEA HOUSE AND STARBUCKS 在紫藤廬與Starbucks 之間 By LUNG Yingtai 龍應台 Translated by Darryl STERK 石岱崙 |

|

| THE ORCHID CACTUS LOOKS OUT AT THE SEA 曇花看海 By CHEN Yu-hong 陳育虹 Translated by Karen Steffen CHUNG 史嘉琳 |

|

| I TOLD YOU BEFORE 我告訴過你 By CHEN Yu-hong 陳育虹 Translated by Karen Steffen CHUNG 史嘉琳 |

|

| RAMBLIN’ ROSE 流浪玫瑰 By Du Yeh 渡也 Translated by John J. S. BALCOM 陶忘機 |

|

| A MING DYNASTY INCENSE BURNER 宣德香爐 By Du Yeh 渡也 Translated by John J. S. BALCOM 陶忘機 |

|

| SELLING OFF THE LAND OF DREAMS 變賣夢土 By Chan Cher 詹澈 Translated by John J. S. BALCOM 陶忘機 |

|

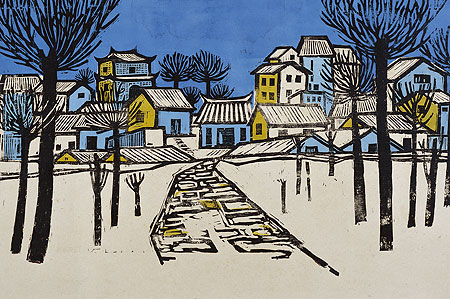

| SHORT ACQUAINTANCE ; LONG MEMORIES —

A RETROSPECTIVE ON CHEN CHI-MAO 「版畫史」誕生在最後的「裝置」裡—— 陳其茂紀念集序 By SHAIH Lifa 謝里法 Translated by TING Chen-wan 丁貞婉 |

|

| PASTORAL SONGS ; POETICAL SENTIMENTS—

CHEN CHI-MAO’S CREATIVE ART

牧歌‧詩情——試論陳其茂的藝術創作 By CHEN Shuh-sheng 陳樹升 Translated by TING Chen-wan 丁貞婉 |

|

| NEWS & EVENTS 文化活動 Compiled by Sarah Jen-hui HSIANG 項人慧 |

|

| NOTES ON AUTHORS AND TRANSLATORS 作者與譯者簡介 |

|

| APPENDIX : CHINESE ORIGINALS 附錄 :中文原著 | |

| THE MONKEYS IN THE WOODEN HOUSE 木屋裡的猴子, woodcut, 79 × 79 cm, 1975 ............................COVER |

|

| A GIRL SLEEPING ON THE RED WALL 石牆上的睡女, woodcut, 53 × 32 cm, 1985.................BACK COVER By CHEN Chi-Mao 陳其茂 |

|

FIRST SNOW OF A RIVER TRIP Translated by Yingtsih HWANG 黃瑛姿 |

||

The airliner touched down on the foggy, wet runway and

slowly taxied to a halt. It had arrived at the airport outside of

town at 6:50. A student of art history, it was my first trip to Xun

county in mainland China, a place famous for its ancient temples. hair in two shoulder-length braids. |

||

|