|

||

|

|

|

|

||

CONTENTS |

|

| THE CHILDREN OF MYANMAR 緬甸的孩子 By CHEN I-chih 陳義芝 Translated by John J. S. BALCOM 陶忘機 |

|

|

GRANNY’S STATE OF MIND 阿嬤的心思 By TING Wen-Chih 丁文智 Translated by John J. S. BALCOM 陶忘機 |

|

| AQUARIUM, WITH TWO SIDETRACKS 水族箱(外二首) By Chang Kun 張堃 Translated by Zona Yi-Ping TSOU 鄒怡平 |

|

| URBAN CHILDHOOD 都市童年 By FONG Ming 方明 Translated by Zona Yi-Ping TSOU 鄒怡平 |

|

| WHITE HAIR 白髮 By Lo Ti 落蒂 Translated by Zona Yi-Ping TSOU 鄒怡平 |

|

| MOTES OF SUNLIGHT— In Gratitude to Ya Hsien 陽光顆粒—謝瘂弦 By Hsiang Ming 向明 Translated by John J. S. BALCOM 陶忘機 |

|

| VISITING THE BLUE GROTTO— Grotta Azzurra, Italy, 1998 航向藍洞 By Jiao Tong 焦桐 Translated by John J. S. BALCOM 陶忘機 |

|

| APRIL 四月 By Hsia Ching 夏菁 Translated by C. W. WANG 王季文 |

|

| FEELINGS RUN DEEP 古井情深 By YANG Wen Wei 楊文瑋 Translated by James Scott WILLIAMS 衛高翔 |

|

| A NOTICE IN SEARCH OF A MISSING PERSON 尋人啟事 By CHANG Ai-chin 張愛金 Translated by Shou-Fang HU-MOORE 胡守芳 |

|

| YOUTH IN NANGAN 少年南竿 By CHIANG Hsun 蔣勳 Translated by Jonathan R. BARNARD 柏松年 |

|

| YOUTH IN TONGXIAO 少年通霄 By CHIANG Hsun 蔣勳 Translated by Jonathan R. BARNARD 柏松年 |

|

| HIROSHIMA LOVE 廣島之戀 By RUAN Ching-Yue 阮慶岳 Translated by David and Ellen DETERDING 戴德巍與陳艷玲 |

|

| FROM “CHINA” TO “TAIWAN” WHAT MESSAGES CAN WE GET FROM THE ART OF LEE MING-TSE? 從「中國」到「台灣」李明則的藝術給了我們什麼訊息? By Hong-ming TSAI 蔡宏明 Translated by David van der Peet 范德培 |

|

FROM “DANDY” TO “WILD CURSIVE SCRIPT” : FALSE FEELINGS

AND TRUE DESIRES IN THE ART OT LEE MING-TSE

從「公子哥」到「狂草」—談李明則藝術中的虛情真欲 |

|

| NEWS & EVENTS 文化活動 Compiled by Sarah Jen-hui HSIANG 項人慧 |

|

| NOTES ON AUTHORS AND TRANSLATORS 作者與譯者簡介 |

|

| APPENDIX : CHINESE ORIGINALS 附錄 :中文原著 | |

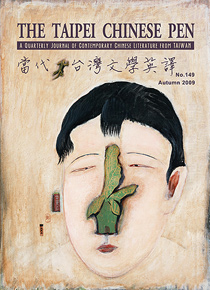

| BLOSSOM OF BANABA 香蕉花, acrylic on paper, 52 × 33.5 cm, 1993...............................................Cover | |

FAIRY 神女, acrylic on paper pulp, 22 × 23 cm, 2008 ..............................................................Back Cover |

|

CHIANG Hsun 蔣勳 YOUTH IN NANGAN Translated by Jonathan R. BARNARD 柏松年

|

| The little island had once been at the frontlines of war.

Those living there grew so accustomed to the sounds of bombs

hitting buildings that they became no longer particularly terrified

of them. Sometimes they’d drink some hard liquor and speak

about the intensity of the previous shelling as if describing a

novel or a film. There was an old sergeant whose shoulder bore

the tattoo “Kill the Pig and Pluck the Hair”─in reference to the

Communists Mao Zedong and Zhu De (the surnames Mao and

Zhu are homonyms in Chinese for “hair” and “pig” respectively).

If a new recruit showed even a glimmer of fear, the sergeant,

red-faced and reeking of booze, would get right in his

face. “Scared?” he’d ask. “Look carefully at this face. Scared?” The recruit would smell the strong scent of alcohol mixed with the rancid stench of rotten food from the sergeant’s mouthand stomach, as well as the unpleasant body odor emanating from his armpits. The putrid mix was almost nauseating. As he neared, it became impossible to breathe. But the young soldier wouldn’t dare step back or turn his head. He’d know that the sergeant’s visage, like the buzz and bang of the shells coming in from all directions, was inescapable. “Ha, ha ha . . . ” The sergeant would laugh crazily, his spit covering the recruit’s face. Suddenly, he’d grab the recruit’s lapel, almost lifting the skinny youth off the ground. “When you hear the buzz of the bomb, don’t panic. Listen carefully. Whatever direction it’s coming from, run the opposite way. Run as fast as you can. When you hear it getting close, get face down quick.” The sergeant would release his hold on the recruit and throw himself down. He’d turn his head and ask the greenhorn: “Did you see? You have to be that fast.” Then, like a wild animal, he’d pull down his pants to expose his dark butt. “Look! he’d bark. “If you’re slow, this is what happens. . . . ” The recruit could see a scarred area the size of a bowl on the sergeant’s dark butt. It resembled a shrunken, wrinkled image of a depressed person’s face. The sergeant would pull himself up from the ground, his pants still down around his legs. He’d slowly stand up, tuck his penis and testicles into his pants and refasten his belt. Then he’d sit next to the recruit and gaze at the sky for a while, listening to the faint sound of the wind. “They’ve finished bombing for today,” he’d tell him. “We’ve got through it.” Observing the recruit’s pallid face, he’d say: “Don’t be scared. So long as you’ re alive, there’s nothing to be frightened of.” Back when the island was under constant bombardment, the commanding officer decided to dig tunnels underground and into the cliffs. Originally, the plan was to create bunkers to store weapons or to install machine guns or antiaircraft artillery. As the bombing grew fiercer, it was gradually decided to extend the excavations, creating tunnels or larger spaces to store both armaments and regular supplies for everyday living. If the military situation were to grow dire, military personnel and island residents could also be evacuated into the tunnels. The tunnels were dug over a 20-year period. Like the passages of an anthill, they were constantly growing, spreading upwards and downwards, winding like goats intestines. Passing through one layer after another of the cliff, they now seemed to hide within them some of the indescribable absurdities of the wartime state of mind.He had watched the tide come in and out that day. Fishermen worked in synch with its ebb and flow. A city boy, he hadn’t known much about the ocean. It wasn’t until he visited Nangan that he gained an understanding of the sea and fishermen, who made their living from it. He learned that the tides were like the ocean’s breathing. Based on this breathing, fishermen decided when to sail and when to return and where to drop anchor and set their nets. “The tidal flats at the mouth of the Minjiang River offer big hauls, and the fish, clams, shrimp and crabs from there are especially sweet and tender.” So the fishermen told him. He thought about the goose barnacle, which he loved to eat. It was known as “Buddha’s hand shell” for its claw’s resemblance to the Buddha’s hand citron. It’s a small shellfish, about the size of a thumb, with a hard claw on one side and a soft shell on the other. Its delicious meat tastes even sweeter when washed down with the island’s strong rice wine. He chatted with the fishermen in the harbor and then checked the time before setting off on his bike toward the tunnels on the north coast. Pedaling uphill was hard work, and he kept to the shade of the she-oaks to avoid the strong sun. Yet he still became drenched with sweat, so he pulled off his shirt and rode barebacked, welcoming each gust of wind. At the top of the ridge, he took a left. Now it was all downhill. He kept his hand off the brake to let the bike roll free, and the wind blew harder and harder against his body. In the distance he could already make out the deep blue sea, which seemed sleepy. Several reefs lay peacefully there. At the entrance to the tunnel there was a two-meter high statue of a few uniformed soldiers laboring with shovels and pickaxes. The work was realistically rendered, and when he looked carefully he could tell that the soldiers were all around 20 years old. He thought for a moment and realized that his father ought to have been the same age when he came here to perform his military service. His father had often recounted to him how they had worked in the tunnels─how they would calculate how much space they wanted to excavate before chiseling small holes at a few marked spots. Granite is extremely hard, and their metal tools clanged and brought up clouds of sparks as they smashed against the rock. “I would stuff some homemade explosives into the small cracks we had labored so hard to make. On the sergeant’s orders we’d light the fuses all at once, exploding the rock to bits. . . .” He remembered the expression of his father, who had been lying in a hospital bed, his liver cancer at its terminal stages. Suddenly his dad loved to talk, and he would offer detailed descriptions of all the soldiers he knew on Nangan Island. He especially enjoyed describing that sergeant with the pockmarked face who, after drinking,.... |

|

All Trademarks are registered. ©2005 Taipei Chinese Center All rights reserved. Best viewed with IE and Netscape browser.